16 May

Final Statement

3 May

Who comes with a standard?

If there will be (PH)EV’s out there, there will be batteries in it, in some form. These batteries are being heavily researched and there are a few plausible candidates that seem to be -technically- ready for the challenge. But what about standards? If we really want to have EV’s in mass production, a lot of standards will have to be set to allow there cars to be used. Standards will have to be set for the battery packs themselves, for the way they will be charged, for the way they’ll be swapped, etc…

Battery packs: Will there be lots of different battery packs? Will each car type have a different pack, or will every manufacturer have their own packs? How big and how heavy will they be? What capacity will they have? What chemistry will they use? How long will they have to last? Who will pay for them?

At the moment, each manufacturer seems to be designing their own packs, indeed. Their dimensioning differs, depending on the application of the car, the cost of the car, etc.. Relatively small battery packs appear in hybrid vehicles, such as the Prius. But for purely electric vehicles, bigger packs are obviously needed. Big packs are very expensive at the moment. Renault states they would be in the range of approx. EUR 11000 (USD 15000) and has plans to lease the packs to customers. They plan to lease a battery pack for approx. EUR 80/month. This means, over 10 years, 12 months a year, this yields approximately the EUR 11000 costs of a pack. But this intrinsically means, a pack would have to last a least 10 years. EUR 80/month + the cost of the electricity to charge the pack, would magically match the costs of the fuel to drive about 1500 km’s a month. This seems to add up, and be a direct, affordable replacement. Other manufacturers are opting for other solutions. Green Stop, Think Car and Better place are other companies investing in battery leasing.

Charging: How will those packs be charged? Using a household outlet, using special charging stations? Will there be any tax to pay? Will there be fast-charging, or will charging take 6 to 8 hours?

Swapping: Some ideas exist to not charge the pack in the car, but take it out, and swap it with an already charged pack. Who will do this? How can the capacity be guaranteed? Who will set the standard for the packs to be swapped?

Better place is a company that tried to provides standards for charging and swapping of battery packs. They say the only way to extend the range of an EV in less than 10 minutes – and that’s what customers want – is by swapping the battery packs. Two different options must thus be provided: battery charging (slow) and battery swapping (fast). Charging could be done when the car is parked, and swapping in a service station, when longer trips are made. According to their website, 8 years and 2000 recharges is what they target the battery packs at.

Household outlet charging is not likely to be allowed in EVs. Currently a huge amount of taxes is imposed on fuels, which will have to be compensated for, if their consumptions is to decrease. Therefore it’s likely cars will have to charge their battery packs with taxed electricity only.

It is clear that a lot of things will have to be standardized, and a lot of companies are trying to get some standards ready. It still seems that no international agreements have been made on a lot of the subjects touched in the above blog. Therefore, we will most probably see a lot of different solutions emerging in the coming years, and all of these will try to set ‘the standard’. Time will tell which ones will survive, and which ones will not…

References:

http://www.france5.fr/c-dans-l-air/index-fr.php?page=resume&id_rubrique=1254

http://www.betterplace.com/solution/batteries/

17 Mar

Battery cost is as important as their energy

When different battery technologies are compared, one often falls back on a comparison of either energy, power or cycle life. While these are certainly important factors, it may not be enough to choose the battery type of the future. In this comparison, we will use the required power/energy as a constant and explore the other factors. This allows to evaluate different battery types in the same application.

The first factors that should be taken into account are volume and weight. This is a factor that is mostly described in terms of energy density, volumetric and/or gravimetric. The importance of the volume is fairly obvious since space in a (hybrid) electric vehicle is limited, certainly if you focus on an aerodynamic design. As stated in our previous blog-post, the weight is a factor that has a big effect on the range of an electric vehicle. Batteries with a high weight, and thus a high gravimetric energy density, can get a higher range for the same energy stored in the batteries. With these factors in mind, Lithium-Ion and Lithium-Polymer batteries have a huge advantage over traditional battery types such as Lead-Acid and Nickel-Metal Hydride.

While volume and weight are logical factors to consider and are often referred to in studies, the battery cost is often neglected. The Lithium-Ion battery technology was first released by Sony in 1991, over the last two decades huge increases in performance, safety and cycle-life have been achieved. While this are very important improvements, they all came with an increase of production cost. The result of these two decades of research is a very broad spectrum of possible combinations of energy density, cycle life and capacity. No one doubts that these batteries are improved since their first design, but the total improvement is only 8% to 10%. If you want to take the most advantage of these technologies however there is a serious price tag coming with it. The standard Lithium Ion batteries have a cost of $0,45 to $0,55 per Wh, high-end types have prices up to $1,50 per Wh. Lithium Polymer batteries are the cheapest alternative available with still a decent performance at $0,35 per Wh.

Lead Acid batteries exist for many years (their first appearance was around 250BC!), but until the late 1960’s, no significant improvements have been made. During the last three decades, a lot of research has been done by Axion in America and CSiro in Australia. The results of these studies are high-end Lead Acid batteries. Axion has developed a PbC-battery that claims an increase of 400% in power at a double of the cost of standard Lead Acid batteries: $0,20 to $0,30 per Wh. The CSiro research resulted in a so-called “ultrabattery”, which is a hybrid of a Lead Acid battery and a super capacitor. In a 100 000-mile test, the ultrabattery got a decrease in gas mileage of 2,8% over the original Nickel Metal Hydride battery pack, but this while saving $2000 in cost.

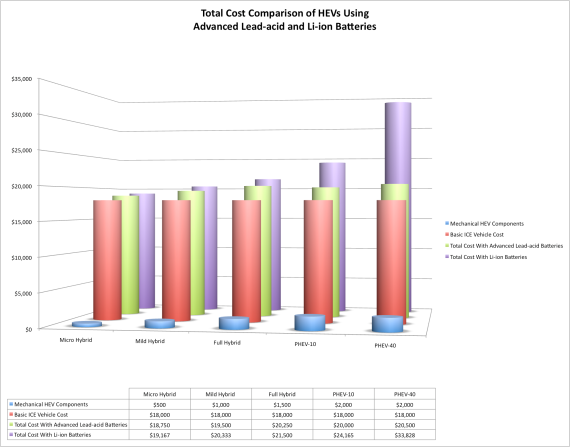

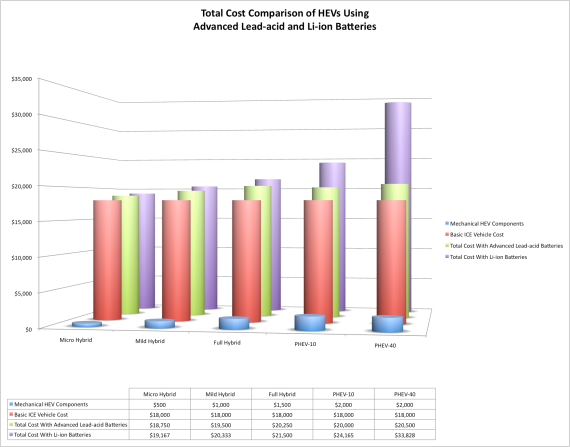

If we use this data to make a comparison between (hybrid) electric vehicles based on their battery choice and capacity, we see that the advantage of Lithium-batteries is smaller than thought. In table 1, an overview of the cost estimates for different battery packs has been made, and it is clear that for the same energy, Lead Acid batteries are a lot cheaper than their Lithium Ion counterparts.

| Battery Capacity (kWh) | Li-Ion Cost | Advanced PbA Cost | PbA Cost Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0,50 | $667 | $250 | $417 |

| 1.00 | $1,333 | $500 | $833 |

| 1.50 | $2,000 | $750 | $1,250 |

| 5.00 | $6,665 | $2,500 | $4,165 |

| 16.00 | $21,328 | $8,000 | $13,328 |

This difference in price plays an important role in the price of the electric vehicle; electronics and the power train are roughly the same for both designs, and thus the cost of the vehicle is largely related to cost of the battery pack. This difference can be seen in the following graph, depicting the cost of the different components of a vehicle and the total cost using either Lithium Ion or advanced Lead Acid batteries.

The conclusion of this blog post is that despite it might be too early to draw a final decision, the focus everyone seems to place on Lithium Ion batteries for the future seems to be a little bit hasty. The costs of the total should be taken into account when comparing the different technologies. Every technology will probably have its use, but for high power applications, Lead Acid shouldn’t be written of despite their higher weight/lower energy density.

10 Mar

Batteries have too low energy densities

Electric vehicles are the way to go for a number of reasons. A few of these are the multitude of electric energy sources available (hydrogen cells, PV arrays, outlet power, …), the high efficiency of electric motors, the inherent green character of electric vehicles: no emmission, etc…

An important question arises though: Can one carry as much electric power, as is possible with conventional fuel-powered cars?

The short answer is: no.

The long answer:

When looking at energy densities of batteries and fuels [1], it is clear that at this point even the best batteries have energy densities two orders of magnitude lower than liquid fuels. E.g. newest commercialy available lithium-manganese batteries have an energy density of about 1 MJ/kg or 230 Wh/kg, the batteries used in the newest Belgian solar car had an energy density of about 180 Wh/kg whereas conventional gasoline has an energy density of about 44 MJ/kg or 10.000 Wh/kg.[2] Does this mean there is no future for batteries in electric vehicles?

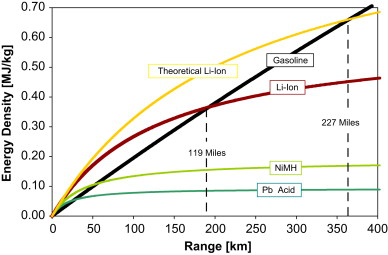

Not neccesairily. What we need to consider is net mechanical energy delivered to the wheels, and not gross caloric energy stored. This means we need to include contributions from regenerative brakes, take into account frictional losses in the transmission, the weight of the motor and transmission, the electrical control and power converters, transmission, exhaust, and all associated parts and fluids, which are necessary to convert the stored energy to mechanical work. The total weight is a lot lower for electric vehicles (no transmission, exhaust, lighter motor,…), than it is for classic cars. [3] This gives a whole different figure:

Important on this graph is that Li-Ion has a higher energy density compared to gasoline for lower ranges. An important point on this graph is the crossover range, where both Li-Ion and gasoline have the same energy density. Where this point lies, is dependent on the type of car or truck considered. The more overpowered a vehicle is (like sports cars, trucks, SUVs) the greather crossover range will be. The gasoline curve is more linear because increasing range means increase the size of the fuel tank, which only add slightly to the vehicle mass. Increasing the range of an electric vehicle means increasing the size of the battery pack, which has a pretty poor energy density, as seen above. This makes it clear why electric vehicles are efficient on the lower ranges. This also explains why it’s more difficult to achieve a big range for small, light cars, while maintaining a better energy density than classic cars.

Another conclusion that can be taken, is that for electric vehicles to have a high range, they need to be light, and need better aerodynamics. This can be achieved by using more composite materials in the construction of cars, and pushing aerodynamic studies way further.

And what about hydrogen fuel cells? As can clearly be seen on the topmost figure, hydrogen has an incredibly high energy density per mass. The big downside is that hydrogen has an equaly incredibly low energy density per volume. Hydrogen is a gas, and it can be compressed, but then still, has a very poor volumetric energy density compared to gasoline. Therefore we believe that hydrogen fuel cells are not a one-on-one replacement for gasoline, but could be a valuable addition to electric cars, combined with e.g. batteries and PV cells on the roof.

[1]: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Energy_density

[2]: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gasoline

25 Feb

Tesla’s Model S is designed for quick battery swaps

One of the most successful electric vehicles is the Tesla Roadster. The new Tesla, an all-electric car named Model S, has been designed so that a

battery pack can be swapped in five minutes or less. This was confirmed by the director of vehicle engineering and manufacturing in an interview in September 2009.

This step forward from Tesla tries to address the main issue with battery-powered vehicles, it takes a very long time to charge the battery pack required to drive a modest distance. During the Global Green Challenge, the Tesla Roadster set a new distance record on a single charge by driving about 500km without charging or swapping the batteries. However, the time required to fully recharge the battery pack is still 30 hours on a conventional power outlet or 5 hours on a high-power (80 Amperes) source.

If Tesla wants to keep selling their plug-in electric vehicles, they need to concern this issue. And one of the solutions could be to provide easy-swappable battery packs. However they will still need to provide an infrastructure that allows this swapping, because it is not recommended to do this at home because of the required equipment. And so this transforms into a chicken or egg story, will anyone invest in these swapping-spots until there are enough vehicles out that can benefit from such a service, and will anyone buy a 50000$ car if they can’t drive more than 500km without having to wait almost an entire day for the batteries to be recharged.

24 Feb

Welcome

Welcome to our MyStatement blog. We, Jonas Lejeune and Maxime Vincent, are writing our Masters Thesis about the development of a battery management system for lithium-polymer battery-packs. These battery packs are mostly used in electric vehicles because of their high energy density compared to other battery technologies. On this blog, we want to find out if it there is a future for electric vehicles with battery packs. We will do this using blog posts which will each focus on different aspects of the use of batteries in electric vehicles.